NAWR • NOW | NESAF • NEXT | GORFFENNOL • PAST

james rielly

tŷ hyll

25|10 - 30|11|24

-

‘James Rielly is something far more damaging than a political artist: he is an artist in motion sporting a mischievous smile’ - Sema D’Acosta + Juan Jesús Torres

[English below]

Mae TEN yn falch o gyflwyno arddangosfa unigol o waith newydd gan James Rielly, ei gyntaf fel rhan o stabl yr oriel, a’i gyntaf yng Nghymru ers dros ddegawd. Yn un o YBA’s nodedig y 90au â’i waith yn rhan o gasgliadau megis Tate, Saatchi ac Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru, magwyd Rielly yng Nghaergybi ac mae bellach yn byw yn Ffrainc gan arddangos ei waith ledled y byd

Mae Tŷ Hyll yn cynnwys cyfres o baentiadau olew ar gynfas, wedi'u gessio'n drwm ac wedi'u paentio'n gain. Yn debyg i ffresgoau crefyddol, gwelwn fotiffau cyfarwydd sy’n dychwelyd dro ar ôl tro – rhai o’r rhain yn bresennol drwy gydol gyrfa Rielly – ei eiconograffeg ei hun yn cynnig damhegion cyfoes

Mae’r paentiadau hyn yn ymddangos fel ciplun o naratif parhaus, moment o chwedl werin ddirgel a chynhenid dywyll. Maent yn troedio’r ymyl rhwng y rhyfedd a'r cyfarwydd heb unrhyw gyd-destun amlwg, ar yr un pryd yn fygythiol ac yn giwt, yn siglo rhwng trasiedi a chomedi, ac yn glanio'n sgwâr ar yr angenrheidiol. Maent i gyd yn agos-atoch o ran maint ac yn tynnu sylw'r gynulleidfa - ar brydiau mae'r llygaid yn cwrdd â'n syllu ni, wrth i eraill guddio'n gyfan gwbl y tu ôl i fwgwd, yn chwareus ond yn anghyfforddus

Mae unrhyw ffigurau adnabyddadwy yn fechgyn - yn nodweddiadol fywiog a chorfforol - ar drothwy llencyndod lletchwith. Mae’r paentiad ‘Sant Cybi a Sant Seiriol Together in Silent Prayer’ yn darlunio – yn ôl pob tebyg y seintiau Cymreig o’r 6ed ganrif - fel dau fachgen mewn barfau gwynion ffug, mwy fel brodyr cynllwyngar na phererinion duwiol. Rydym yn ymdrin â’r gwaith gyda’n ffynonellau diwylliannol ein hunain, gan chwilio am gyd-destun a ‘bachau’ i’w deall – mae’r tŷ sy’n llosgi yn ‘Croeso i Gymru’ yn sylw ar weithredoedd Meibion Glyndŵr a’u dinistr o dai haf ym mro mebyd Rielly - onid yw?

Hiwmor yw'r nodyn cyffredin, ac mae Rielly yn defnyddio'r hiwmor hwnnw fel arf i ddod â ni yn agos. Y thema mawr yma yw ni fel bodau dynol, ein cyflwr dynol a'r byd rydyn ni wedi'i ddinistrio i ni ein hunain. Trwy bwyntio at mor chwerthinllyd yw’r cyfan a gwatwar abswrdiaeth a thristwch bywyd modern, mae dychan melys Rielly yn rhoi’r byffer y mae angen arnom inni edrych ar ein hunain heb golli gobaith – a dysgu ein gwers, gobeithio. Mae'n cynnig mecanwaith ymdopi i ni - os na fyddwn yn chwerthin, byddwn yn crio

•

TEN is pleased to present a solo exhibition of new work by James Rielly, his first as part of the gallery stable, and his first in Wales in over a decade. Now living in France, Rielly grew up in Holyhead, North Wales and regularly exhibits internationally with his work part of major public collections including Tate, Saatchi and the National Museum of Wales. Rielly was active in the 90s London art scene as one of the notable YBA's.

Tŷ Hyll includes a series of oil on canvas paintings, heavily gessoed and delicately painted. Akin to religious frescos, we see familiar and reoccurring motifs - some of these present throughout Rielly’s career - his own-made iconography offering modern-day parables

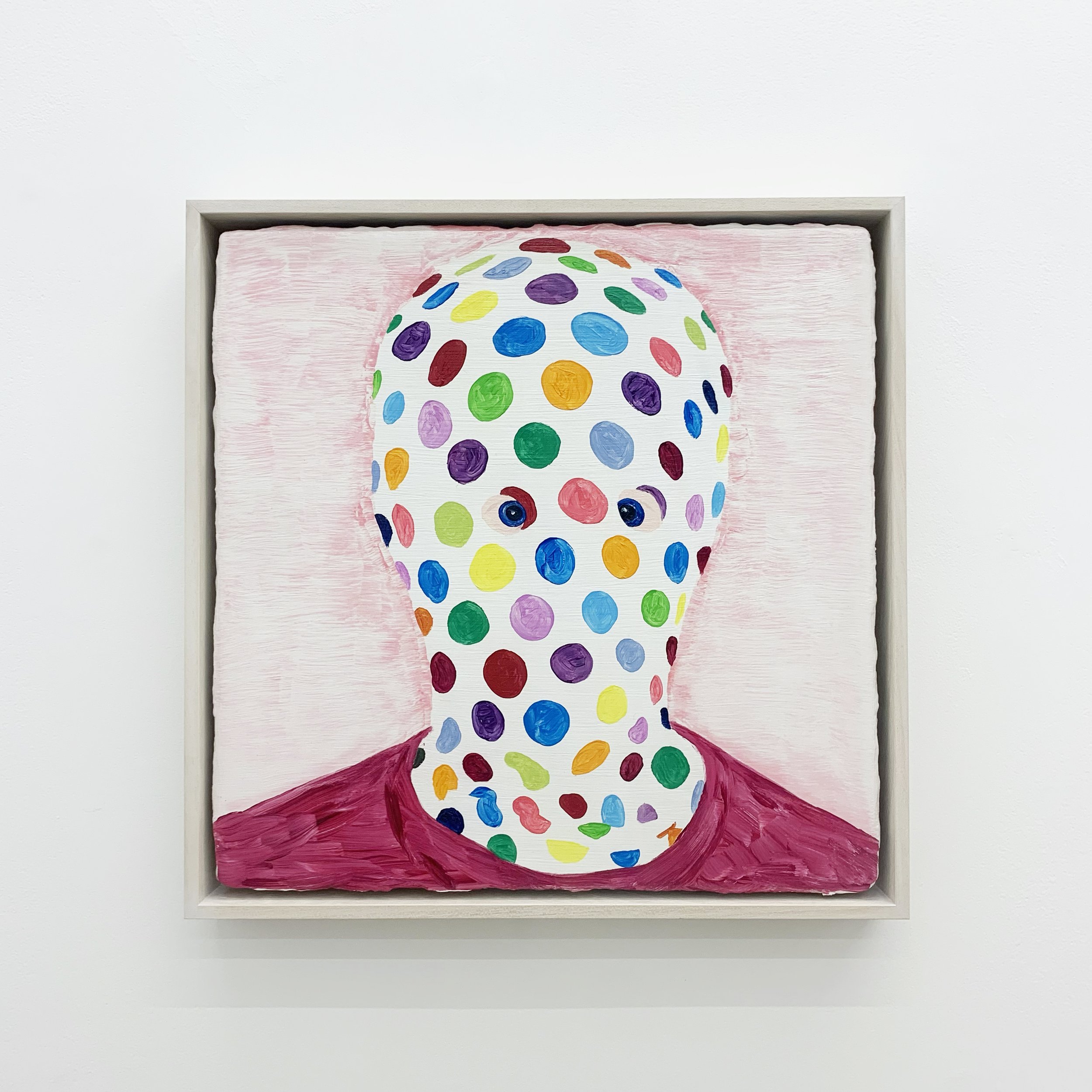

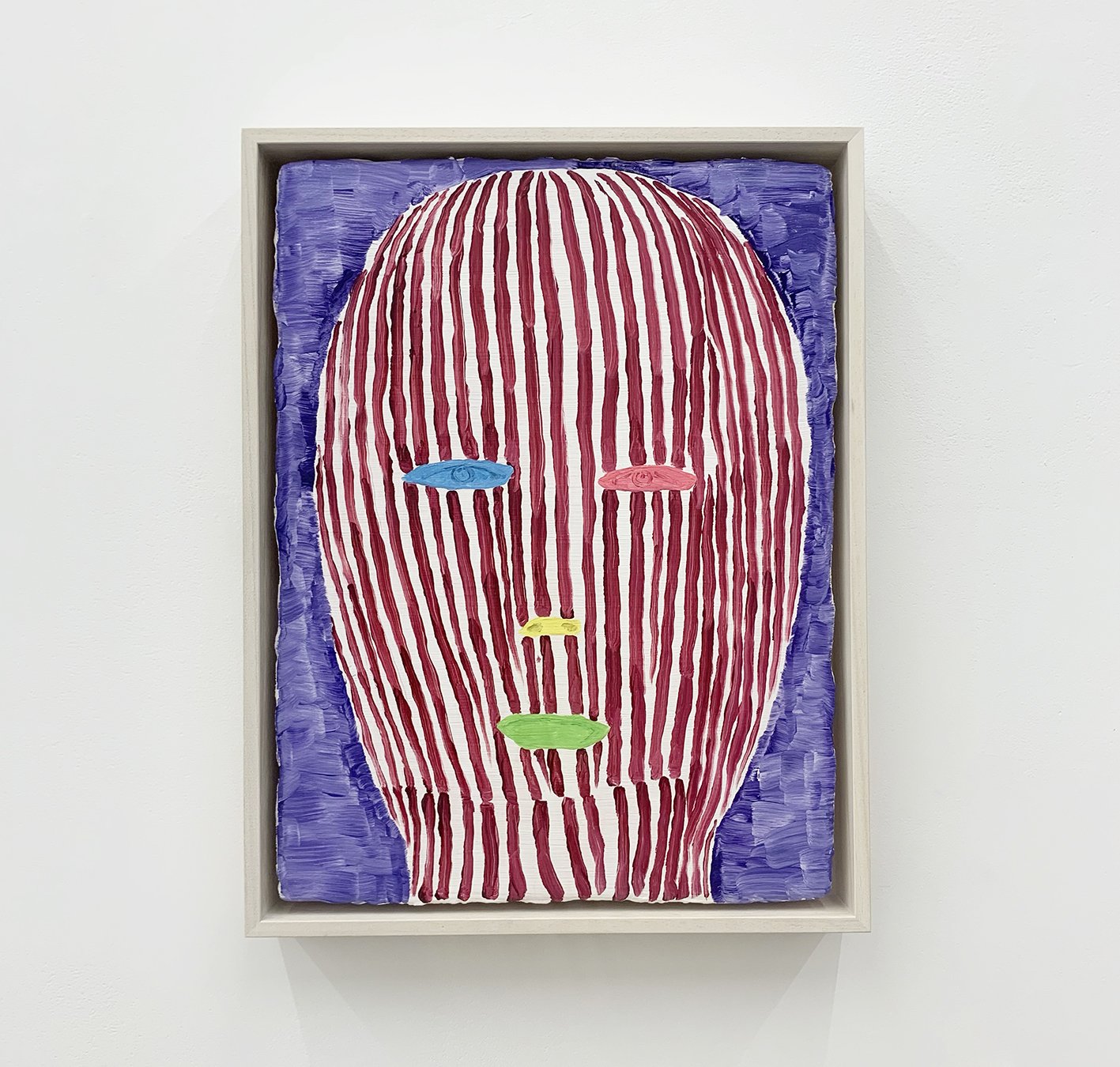

These paintings appear as a snapshot of an ongoing narrative, a ‘still’ of a fantastically mysterious and inherently dark folk tale. They tread the edge of the bizarre and the familiar with no obvious context, simultaneously threatening and cutesy, swaying between tragedy and comedy, and landing squarely in the wholly relevant. All are intimate in scale and draw in the viewer - at times the subject meets our gaze as we look, others hide completely behind a mask, playful yet unnerving

Any recognisable figures are boys - typically boisterous and physical - on the cusp of awkward adolescence. The painting ‘Saint Cybi and Saint Seiriol Together in Silent Prayer’ depict - presumably the 6th century Welsh saints - two boys in fake white beards, more scheming brothers than pious pilgrims. We approach the work with our own cultural points of reference, looking for context and ‘hooks’ to understand. The burning house of ‘Croeso i Gymru’ is a comment on the actions of Meibion Glyndŵr and their destruction of holiday homes in Rielly’s own home county - is it not?

Humour is the prevalent note, and Rielly uses that gallows humour as a common tool to bring us in. The overarching theme here is that of us humans, our human condition and the world we have destroyed for ourselves. Through pointing at the ridiculousness of it all and mock-laughing at the absurdity of modern life, Rielly’s sugar-coated satire gives us that buffer we need to look at ourselves without loosing hope - and to hopefully learn our lesson. He offers us a coping mechanism - if we don’t laugh, we’ll cry

-

Gan • Written by Mike Tooby

The group of new paintings that James Rielly is showing at Gallery TEN are small works in oil on canvas. They are a group chosen from the studio for this exhibition. They are not, as has sometimes been the case, a single work made up of a number of smaller paintings.

The title, ‘Tŷ Hyll’ refers to the exhibition as a whole. As many who know Snowdonia will recognise, it refers to the small cottage made of massive stone lumps, tucked into a plot under a steep mountainside and next to a busy road. The artist explains that he passes Tŷ Hyll as he drives to and from his family home in North Wales.

Tŷ Hyll is usually translated as ‘Ugly House’.

‘Tŷ Hyll’ is a title that Rielly has used before, for an exhibition in north Wales in 2014, curated by the artist Emrys Williams, and two subsequent exhibitions in France.

At first it directs our attention to three pieces in this exhibition which explicitly reference Wales ( it is the case that all his pictures depicting buildings only have Welsh titles). Here, one is a quasi mythic invocation of storms and castles. Two are an image of a house, small, cosy, perhaps best described as a cottage, where a frightening drama has occurred. In ‘Croeso i Gymru’ flames released from inside are climbing above the roof. In ‘Welsh Village 21 October 1966’ a pile of black engulfs the cottage, the title bearing the date of the disaster in Aberfan.

This last painting returns to the motif of ‘Partially Buried’, one of the two major paintings by Rielly that are in the collection of Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. It speaks of the recurrence of this image in the artist’s mind. The two companion pieces in this exhibition make an intersection with it, by suggesting other ways that the security or attractiveness of the domestic can be shaken by forces from without.

Rielly enjoys the way Tŷ Hyll has many stories that attach to it: that it was built overnight so that the builders could claim its land; or that it was a base for highway robberies. ‘Hyll’ may in fact not even originally derive from describing the cottage. It might just be a corruption of the name of the river nearby. One might certainly enjoy the paradoxes involved in its celebration in Snowdonia’s ‘heritage’ landscape : as a website post says – “Join us at the lovely Tŷ Hyll”.

That ambiguity – between the apparently safe and charming and the unsettling and disturbing, is also well known and widely seen as a distinguishing feature of his figurative paintings. Rielly’s other work in Wales’ national Collections, ‘Pet’, is an example, a powerful image of a small girl with a black eye, holding a soft doll, also bearing a black eye.

The present exhibition presents many examples of the figurative, all provoking nuanced versions of this central ambiguity. Central to the achievement of ambiguity is the nature of the painting itself.

We might find his paintings beautiful, full of light, with a wonderful sense of colour. The handling and touch of the brush can be authoritative in the larger scale works, delicate in the smaller pieces. We have to manage this sense of the joy in painting when addressing the singularity of his imagery. This tension is often enhanced by the titles. A head made up of bright stripes faces us : ‘Try to Blend In More’; a head covered (by a cloth?) with coloured spots : ‘Try to be More Desirable’.

While working for the present exhibition and others in continental Europe, Rielly is also involved in a large monographic publication. This will bring together around 200 images of work from across his career. In discussing it, Rielly comments that it has again prompted the question of consistency and evolution in his work.

As well as cross referencing imagery or evolving new but consistent ways of painting, such questions as whether more recent work may (or may not) relate to early experiences and fascinations, or be the product of his education and first achievements in mature paintings, are called forth.

‘I have always collected images and made my paintings/drawings based on these images, found images cut up reworked and changed. This started at a young age. I did not know what I was doing. I always collected images together in scrap books, most of these have long disappeared . I had one with all the newspaper photos I could find about the death of Winston Churchill, this was the first half of a scrap book and the second half was Man from U.N.C.L.E. a tv program I loved. Also I had one just about the Aberfan disaster, as the children where about the same age as me. Others where about Dylan Thomas and so on’.

The richness of his work – and its inter-weaving of motifs and images, media and scale – means that we are not allowed to reach a one-dimensional reading that can be attributed to a single origin story. We might take two aspects of such a story to illustrate.

James Rielly “is a Welsh artist living and working in France.” This simple summary from Wikipedia is often seen in references to his biography. He explains that he grew up speaking Welsh as a small child until he had to speak English throughout his schooling. His Welsh was maintained through the Urdd Eisteddfod: he won prizes for singing, and for art. His making art was encouraged by a teacher involved in the Urdd, giving confidence to the thought that this could be something he could pursue seriously.

What of his more formal early education? Leaving Wales to study at Cheltenham, Rielly then took an MA in art in Belfast, and returned shortly afterwards for a residency in the city. Obviously Belfast in the early 1980s was a complex, challenging environment, and one that provoked much creative energy. Rielly was taught by Alastair MacLennan. MacLennan, with his quiet, thoughtful and gentle demeanour, made vivid durational performances and installations. MacLennan also makes beautiful and uncanny drawings, which transfer the psychological and social power of his time-based work into monochromatic juxtapositions of objects and abstracted gestures.

In asking Rielly questions about moments in his career for this text, he had to break off from sawing and chopping logs in the home he loves, in preparation for an autumn and winter in rural France. Let us, then, take these narrative points of reference – a young person growing up in north Wales, a student and young artist in Belfast, an artist with a long career now living in France – not in a deterministic way, but more as intriguing examples of the many possibilities in which experience and imagination interact in how an artist works.

‘When I started trying to be an artist, I felt I knew what I was doing and why I was doing it. Now I have no fixed idea and most of the time I cannot explain in an easy way what I am doing’.

There is in this new group a work called ‘Blocking Out the Light’. The head seems to turn that one might find wistful, but one can’t be sure given that the eyes for once, do not meet ours. Instead ribbons of colour overlay each other, the shallow space of the image allowing them to float on the surface of the painting. One might say that the image is itself a metaphor for how it is created in the practice of painting.

[Michael Tooby lives in Cardiff and is Professor of Curatorial Practice, Bath Spa University.]

-

Wednesday - Saturday 10:30 - 17:00

The Coach House, Rear of 143 Donald Street, Cardiff, CF24 4TP

+44 (0) 29 2060 0495

-

Artworks can be purchased online or by contacting the gallery.

Ein Celf • Own Art

Own Art is a national initiative providing interest-free credit for the purchase of original artwork. The purchase is split over 10 interest-free instalments, with no deposit, up to £2500.

To purchase an artwork through Own Art contact the gallery to be sent an online form: info@gallery-ten.co.uk | 029 2060 0495

Klarna | Purchase is split over 4 interest-free instalments [option available at checkout]

VAT Prices stated on this website are exclusive of VAT Margin (8.3%). VAT is added at checkout if applicable.

Animations made from a series of watercolour drawings 2013-2019, 3:53min

Blocking Out the Light, 2024, oil on canvas, 41.5 x 31.5cm

view full details